|

November 2008

In this Issue

St

Martin

How to Make Kolyva

|

How well do you know your Saint?

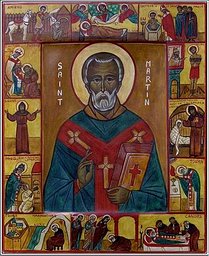

St Martin of Tours

I have

had the name Martin from an early age! I

have never really liked it and as a

youngster thought how nice it would be

to change it – maybe to Steve or Dave

something more up to date. I found by

reading through the lectionary during

sermons at Coventry, that St Martin’s

Day was celebrated on 11th November –

the day after my birthday. I asked Mum

about this but she said it must be

coincidence because she hadn’t chosen

the name by reference to any prayer

books.

So when my Chrismation was afoot, there

arose the possibility of changing my

name. A number of alternatives appealed

– Zacchius sounded fun since he was a

short man and a bit of a comedy

character in my book. Then I thought

about Martin again and did a little bit

of reading about him – particularly the

story about the cloak.

So when my Chrismation was afoot, there

arose the possibility of changing my

name. A number of alternatives appealed

– Zacchius sounded fun since he was a

short man and a bit of a comedy

character in my book. Then I thought

about Martin again and did a little bit

of reading about him – particularly the

story about the cloak.

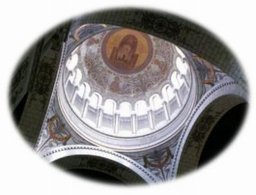

St

Martin seen in mosaic above the

Sanctuary in the Basilica St Martin in

Tours

Giving just half his cloak to a beggar

seemed to ring bells with me – that’s my

sort of generosity: to give a bit of

something but not leave yourself

without! I might manage to emulate this

sort of thing – and that is of course

part of the point of a Name Saint; to

have someone to try to emulate or model

oneself on.

So I stuck with the name Martin after all those years

of wanting to change it.

I was lucky enough to have the opportunity, with

Carolyn, to take a pilgrimage to Tours

in France where St Martin was Bishop,

before attending the enthronement of

Metropolitan John. Now I know more about

St Martin, his life and times, I realise

there was rather more to him than

half-hearted generosity. After all, how

could I have thought that one can become

a saint simply by giving away half a

cloak? There had to be more to it than

that...

St Martin’s Rebuilt Basilica in Tours

Born in 316 in Savaria, Martin’s Father was a senior

officer in the Roman army and Martin

grew up in Ticinum in modern Pavia,

Italy. At aged ten, he went to church

against his parents wishes and became a

catechumen. At this time, Christianity

had only just become a legal religion

but was still a minor faith, with the

cult of Mithras being by far the

dominant religion in the army. When aged

15, Martin was required to join the

cavalry himself and was stationed in

what is now Amiens in France.

It was while serving as a soldier that he impulsively

gave half his cloak to a beggar. That

night he received a vision of Christ

wearing that cloak which Martin had

given away, saying to the angels: “Here

is Martin, the Roman soldier who is not

baptised; he has clothed me.”

So Martin was baptised and refused to

battle with the Gauls at Worms in 336

saying “I am a soldier of Christ. I

cannot fight.” Charged with cowardice,

Martin’s response was to volunteer to go

to the front of the troops unarmed. It

was planned to accept this offer but

peace broke out, the battle never

happened and Martin was released from

military service.

So Martin was baptised and refused to

battle with the Gauls at Worms in 336

saying “I am a soldier of Christ. I

cannot fight.” Charged with cowardice,

Martin’s response was to volunteer to go

to the front of the troops unarmed. It

was planned to accept this offer but

peace broke out, the battle never

happened and Martin was released from

military service.

The church at Candes where Martin died

Martin then became a disciple of Hilary

of Poitiers, a chief opponent of

Arianism and proponent of

Trinitarianism. When Hilary was forced

into exile, Martin returned to Italy to

lead the life of a hermit on the little

island of Gallinaria. When Hilary

returned in 361, Martin joined him again

and Hilary gave Martin a wilderness

retreat. Many people came to see him and

enough stayed as disciples that Hilary

founded a monastery for them called

Legug

where Martin lived until Hilary died. It

was here that Martin performed one of

his first and many miracles. When a

catechumen died before baptism, Martin

laid himself over the body and after

several hours, the man came back to

life. Legug

where Martin lived until Hilary died. It

was here that Martin performed one of

his first and many miracles. When a

catechumen died before baptism, Martin

laid himself over the body and after

several hours, the man came back to

life.

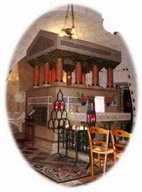

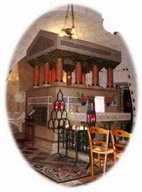

The tomb of St Martin beneath the Altar

in the Basilica

In 371, Martin became the reluctant Bishop of Tours –

hiding from the people in a barn full of

geese. The geese made such a noise that

his hiding place was given away – so he

is the Patron Saint of Geese! Martin

lived not in a palace, but in a cell

attached to a church in the hope of

maintaining the lifestyle of a monk, but

the role of Bishop meant that people

came constantly to Martin with questions

and concerns that involved all the

affairs of the area.

To regain some solitude, Martin withdrew outside the

city to a cabin made of branches. Here

he attracted as many as eighty disciples

who wanted to follow him and so he

established a monastery at Marmoutier

near Poitiers which still survives today

and is the longest operating monastery

in France – and somewhere to visit on my

next trip.

It is easy to suppose that Martin avoided many of his

bishoping responsibilities, but he was

said to be very committed to his people.

One of these responsibilities was, he

felt, to convert those who still held to

non-Christian beliefs. He did not

attempt to convert these people by

preaching from a high pulpit or from far

away, but instead he travelled from

house to house speaking to people about

God. He would then organise the converts

into a community under the direction of

a priest or monk. He would visit these

communities regularly. Of course, he

sometimes ran into resistance. On one

occasion he tried to convince locals to

cut down an old pine tree they

venerated. They agreed, but only if

Martin would sit directly under the the

path of the leaning tree. Martin sat

himself down by the tree and the

townsfolk began to cut away at the other

side. Just as the tree began to fall,

Martin made the sign of the cross and

immediately the tree fell in the

opposite direction – slowly enough to

miss the fleeing people. He made many

converts that day!

The wondrous stories of Martin and his miracles are

worthy of a book in their own right –

indeed his biographer Sulpicius Severus

(c363 – 420) wrote lengthy works, begun

before Martin’s death. There is too much

to repeat in this small space.

Martin died in Candes and although

accounts differ as to the year (between

395 and 402) it was known to be on

November 8th. Monks from Tours came and

stole his body during the night from the

monks in Candes, and he was buried, at

his request, in the Cemetery of the Poor

in Tours.

Martin died in Candes and although

accounts differ as to the year (between

395 and 402) it was known to be on

November 8th. Monks from Tours came and

stole his body during the night from the

monks in Candes, and he was buried, at

his request, in the Cemetery of the Poor

in Tours.

The reliquery for the head of St Martin

from the late 14th Century – now in the

Louvre

Martin’s successor as Bishop in Tours, Bricius, built a

little chapel over Martin’s grave and

then when Bishop Perpetuus took office

in 461 a grand basilica was built as the

chapel was no longer sufficient for the

crowds of pilgrims that were already

coming. Martin was reburied behind the

altar of the basilica, his sarcophagus

placed on a large block of marble to

make it visible. The basilica itself was

160ft long and 60ft wide and contained

120 columns.

Destroyed many times by fire, the basilica was rebuilt

beginning in 1014 and the shrine became

a major stopping point on pilgrimages.

The basilica was finally sacked by the

Huguenots in 1562, then it was

deconsecrated during the French

Revolution, used as a stable and then

its dressed stones sold and a street

built on the site.

In 1860, excavations established the dimensions of the

former basilica and a project for a new

basilica took shape in 1871. The present

building was consecrated in 1925 and

maintains the shrine of St Martin in the

same position as the original basilica,

containing a small reliquery and all

that remains of the relics of St Martin.

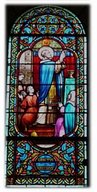

The story of St Martin is everywhere in

this part of France – from depictions in

stained glass windows, frescoes and

carvings to beautiful paintings – and

societies throughout the world concerned

with charity and justice for the poor

and oppressed are dedicated to St

Martin.

The story of St Martin is everywhere in

this part of France – from depictions in

stained glass windows, frescoes and

carvings to beautiful paintings – and

societies throughout the world concerned

with charity and justice for the poor

and oppressed are dedicated to St

Martin.

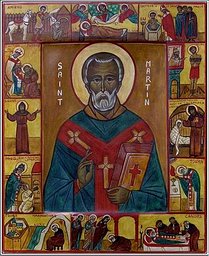

Martin offers up the Host at the Liturgy

Aside from miracles, the introduction of the Chenin

Blanc grape and the technique of pruning

vines is attributed to St Martin – so he

is also the Patron of wine growers, wine

makers and (curiously) reformed

alcoholics. He is also Patron Saint of

the Pontifical Swiss Guards, the diocese

of Rottenburg-Stuttgart and Buenos

Aires. Martin Luther was named after him

as he was baptised on St Martin’s day in

1483.

As the Advent Fast draws near, it is also interesting

to note that from the late 4th century

until the late Middle Ages, much of

Western Europe – including Great Britain

– engaged in a period of fasting

beginning on the day after St Martin’s

Day. The fast lasted 40 days and was

therefore called “Quadragesima Sancti

Martini”. At St Martin’s Eve and on the

feast day, people ate and drank heartily

– the traditional food being, of course,

goose. This fasting time became Advent.

So St Martin is a much more worthy Saint than I had

first imagined – and not as

straightforward to emulate as I had

hoped.

I have a considerable way to go!

Martin Shorthose

|

So Martin was baptised and refused to

battle with the Gauls at Worms in 336

saying “I am a soldier of Christ. I

cannot fight.” Charged with cowardice,

Martin’s response was to volunteer to go

to the front of the troops unarmed. It

was planned to accept this offer but

peace broke out, the battle never

happened and Martin was released from

military service.

So Martin was baptised and refused to

battle with the Gauls at Worms in 336

saying “I am a soldier of Christ. I

cannot fight.” Charged with cowardice,

Martin’s response was to volunteer to go

to the front of the troops unarmed. It

was planned to accept this offer but

peace broke out, the battle never

happened and Martin was released from

military service. Legug

where Martin lived until Hilary died. It

was here that Martin performed one of

his first and many miracles. When a

catechumen died before baptism, Martin

laid himself over the body and after

several hours, the man came back to

life.

Legug

where Martin lived until Hilary died. It

was here that Martin performed one of

his first and many miracles. When a

catechumen died before baptism, Martin

laid himself over the body and after

several hours, the man came back to

life. Martin died in Candes and although

accounts differ as to the year (between

395 and 402) it was known to be on

November 8th. Monks from Tours came and

stole his body during the night from the

monks in Candes, and he was buried, at

his request, in the Cemetery of the Poor

in Tours.

Martin died in Candes and although

accounts differ as to the year (between

395 and 402) it was known to be on

November 8th. Monks from Tours came and

stole his body during the night from the

monks in Candes, and he was buried, at

his request, in the Cemetery of the Poor

in Tours. The story of St Martin is everywhere in

this part of France – from depictions in

stained glass windows, frescoes and

carvings to beautiful paintings – and

societies throughout the world concerned

with charity and justice for the poor

and oppressed are dedicated to St

Martin.

The story of St Martin is everywhere in

this part of France – from depictions in

stained glass windows, frescoes and

carvings to beautiful paintings – and

societies throughout the world concerned

with charity and justice for the poor

and oppressed are dedicated to St

Martin.